Community Environmental Impact Calculator

See how your local actions could create real change based on successful community initiatives from around the world

When people think of environmental groups, they often picture big organizations with offices in capital cities. But some of the most powerful change happens right where you live-in neighborhoods, towns, and coastal communities. These aren’t just volunteers picking up trash. They’re people organizing, lobbying, restoring land, and teaching others how to protect what’s left. Here are five real community-based environmental groups that didn’t wait for permission to act.

The Kaitiakitanga Collective - Bay of Islands, New Zealand

In the Bay of Islands, a group of Māori elders, young surfers, and local fishers formed the Kaitiakitanga Collective after noticing plastic choking the reefs and fish populations dropping by 40% in five years. They didn’t start with petitions. They started with weekly beach cleanups, then trained 80 local kids in traditional Māori stewardship practices. Now, they’ve helped pass a local bylaw banning single-use plastics in all marine access zones. Their biggest win? Restoring a mangrove nursery that now supports juvenile snapper and blue cod. The group runs free Saturday workshops for families, teaching how to identify native species and track water quality using simple pH strips. They don’t take government grants. They fundraise through community art markets and sell handmade kelp-based skincare products made from harvested seaweed.

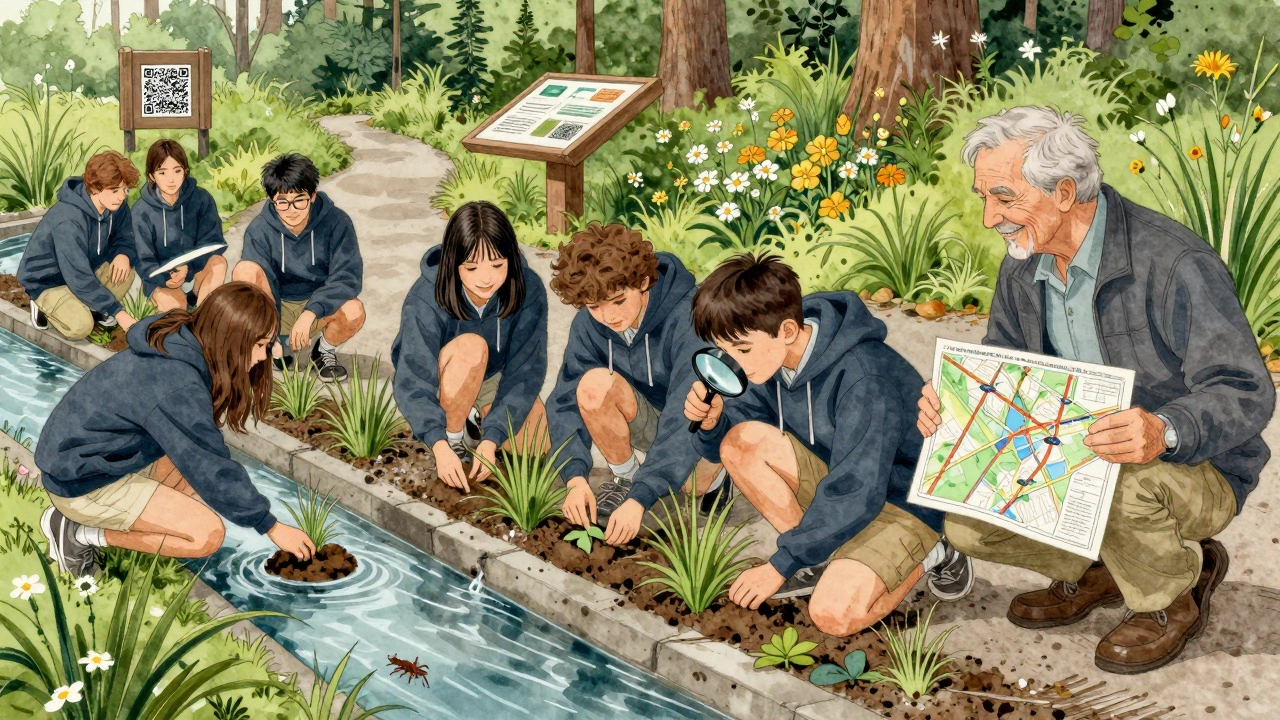

Greening the Gutter - Portland, Oregon

Portland’s urban creeks were buried under concrete, filled with oil runoff, and ignored by city planners. A group of high school students from Jefferson High started Greening the Gutter after their science teacher showed them a 1998 map of the city’s buried waterways. They mapped every hidden creek using satellite imagery and old city plans. Then they convinced the city to let them remove 200 feet of concrete from a section of Mill Creek. They planted native sedges, installed bioswales, and built a small interpretive trail with QR codes linking to audio stories from elders who remembered the creek before it was paved. The city later adopted their model for three more sites. Today, the group runs a summer internship for teens to monitor water temperature and macroinvertebrates. Their data helped prove that urban cooling from restored creeks reduced local heat island effects by 5°F in summer.

The River Keepers - Ganges Delta, Bangladesh

In the Sundarbans region, where rising seas and saltwater intrusion are destroying rice fields, a group of women farmers formed The River Keepers. Most had never been to school. But they noticed their wells turning brackish, their crops failing, and their children getting sick from contaminated water. They started digging small earthen barriers to redirect freshwater during monsoon season. They collected rainwater in lined pits and shared designs with neighboring villages. They partnered with a local university to test soil salinity using cheap, open-source sensors made from Arduino chips. Within three years, they restored 17 acres of farmland and trained 300 women in low-cost water management. Their model is now used by the Bangladesh government’s climate adaptation program. They don’t call themselves activists. They call themselves “water guardians.”

Urban Forest Initiative - Johannesburg, South Africa

Johannesburg lost nearly 30% of its urban tree cover between 2010 and 2020 due to illegal logging and development. A group of retired teachers, mechanics, and students launched the Urban Forest Initiative to plant trees where they were needed most-in informal settlements with no shade and no air circulation. They didn’t wait for permits. They started by planting 500 indigenous trees like marula and knobthorn in vacant lots and along sidewalks. They taught residents how to water trees using recycled plastic bottles with slow-drip holes. They turned tree planting into community events with music and food. Within two years, they planted over 12,000 trees. Local schools now use the groves for outdoor science lessons. The city eventually gave them land for a permanent nursery. Their trees are now monitored by community members using a simple app that logs growth and damage. One grandmother told a reporter: “My grandchildren used to be afraid of the street. Now they run to the trees.”

Coastal Cleanup Crew - Tofino, British Columbia

Tofino, a small fishing town on Vancouver Island, saw plastic waste washing up in record amounts after a series of storms in 2022. A group of surf instructors, Indigenous fishers, and retirees formed the Coastal Cleanup Crew. They didn’t just collect debris. They cataloged every piece-bottles, fishing nets, toothbrushes, even a child’s shoe. They partnered with a marine biologist to track where the trash came from. Their data showed 68% came from distant shipping lanes, not local tourists. They used that evidence to lobby Transport Canada for stricter waste disposal rules for cargo ships. They also started a “Plastic Passport” program: every piece of plastic collected gets tagged with a QR code that links to its origin story. Schools use these in geography lessons. The crew now trains 200 volunteers a year and has helped reduce beach litter by 72% in three seasons. Their motto? “We don’t clean beaches. We fix systems.”

What Makes These Groups Different?

These aren’t charities asking for donations. They’re networks of people who saw a problem and built solutions with what they had: time, local knowledge, and stubborn hope. They use science, but they don’t wait for labs. They use policy, but they don’t wait for politicians. They start small-sometimes with just a shovel, a bucket, and a group of neighbors.

What they all share is this: they measure success not in funding raised, but in trees planted, fish returned, children taught, and water cleaned. They don’t need global fame. They need their community to show up.

How to Start Something Like This

If you want to start a local environmental group, here’s what actually works:

- Start with one visible problem-not “climate change,” but “the creek behind the school is always oily” or “the park has no benches and no shade.”

- Find three people who care-even if they’re not experts. One person can draw maps. Another can take photos. A third can talk to the mayor.

- Document before you fix-take pictures, record water samples, count litter. Data beats emotion every time.

- Make it easy to join-host a cleanup on a Saturday morning with coffee and snacks. No sign-ups. No forms.

- Share your win-even a small one. A photo of a restored patch of wetland. A child holding a fish they helped release. That’s what keeps people coming back.

Why This Matters More Than Ever

Global environmental problems feel overwhelming. But every major change-from clean air laws to protected forests-started with people who refused to wait. These five groups didn’t have millions of dollars or fancy offices. They had neighbors, determination, and a belief that their patch of earth mattered.

The next environmental breakthrough won’t come from a UN summit. It’ll come from someone in your town who looked out their window and said, “That’s not right.”

Can small community groups really make a difference in environmental protection?

Yes. Groups like the Kaitiakitanga Collective in New Zealand and the River Keepers in Bangladesh restored ecosystems, influenced policy, and changed local behavior without big budgets. Their impact comes from consistent action, local knowledge, and community trust-not funding. Studies from the World Resources Institute show that community-led initiatives are 30% more likely to sustain results over five years than top-down projects.

Do I need to be an expert to start an environmental group?

No. The Urban Forest Initiative in Johannesburg began with retired teachers and mechanics. What matters is curiosity, willingness to learn, and the ability to ask for help. Many groups partner with universities, local councils, or NGOs for technical support. You don’t need to know everything-just how to get people together and start doing.

How do I get my community to join a local environmental effort?

Make it easy, social, and rewarding. Host a cleanup with free coffee and music. Turn it into a family event. Share before-and-after photos on social media. Celebrate small wins-like planting 50 trees or removing 200 bags of trash. People join when they see progress and feel included, not when they’re told it’s their duty.

What’s the best way to measure the success of a local environmental group?

Track tangible outcomes: number of trees planted, liters of water cleaned, pounds of plastic removed, number of people trained, or species returned. Use simple tools like free apps (e.g., iNaturalist for species tracking) or hand-counted logs. Success isn’t about funding-it’s about lasting change in your area. If kids are now playing near a stream that used to be toxic, you’ve won.

Can community environmental groups influence government policy?

Absolutely. The Coastal Cleanup Crew in Tofino used collected data on plastic sources to push Transport Canada to change shipping waste rules. The Kaitiakitanga Collective helped pass local plastic bans. When communities document problems clearly and show consistent action, governments listen. Policy change often starts at the local level before scaling up.

What Comes Next?

If you’re inspired, don’t wait for the perfect plan. Grab a trash bag. Walk around your neighborhood. Talk to someone who’s lived there longer than you. Start with one thing. The world doesn’t need more people waiting for someone else to act. It needs more people who look around and say, “I’ll start here.”